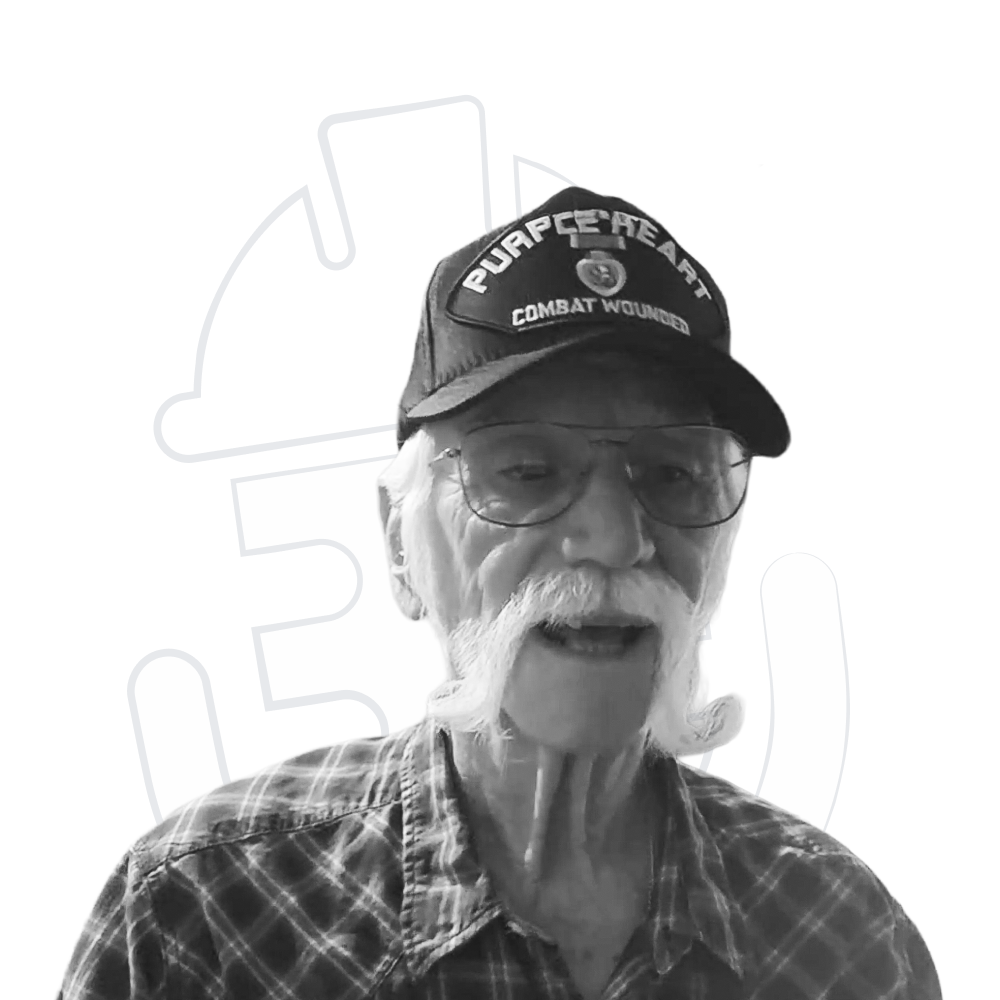

RL (00:00) So at 18, I couldn't drink, I couldn't vote, I couldn't be a lineman, but I could be a lineman's helper, what they are, we affectionately refer to as a grunt. RL (00:13) 90% of the rules are written for of the employees. as a Vietnam veteran and an Army veteran, I really have a soft spot in my heart for old soldiers. there's normally two types of rule. One of them is a should rule. This is a good idea, but you can deviate from it if there's a good reason to. The other one's a shall rule, which says this carries the force of law. We don't have the authority. We have to follow this to the letter. Now I do ride over to Houston on occasion and watch, the Astros play because I, you know, they're kind of, they're only about a couple hours away and kind of a hometown team. So I do like the Astros. Hari Vasudevan (01:01) Welcome to a new episode of From Boots to Boardroom. Not every leader sits in a corner office. From Boots to Boardroom shares the journey of those who power America from the job site to the boardroom, leading with grit, tenacity, empathy. and vision. Today's episode is sponsored by kyro ai Digitize work and maximize profits. For more information visit kyro.ai. We have a very special guest today. Our guest is R.L. Grubbs. You can see him wear his purple heart cap. Thank you for your service. RL, super quick intro here. â“ RL has more than five decades in the industry. RL, as he likes to say, stands for real lineman. Right? You've seen many, positive changes in the industry from the time his career started way back in the mid 60s. And, you know, he's seen the RL (01:58) you Hari Vasudevan (02:10) improvement in safety from you know the number of deaths of linemen in the trade used to be 50 percent. So one in every two linemen pretty much knew that they were going to die to the latest metrics is one in every 2,000 so 0.05 percent. That's a significant change and I'd love to know more about how RL has seen the evolution of safety in the workplace. He's a certified CUSP. He's a certified OSHA 10 and OSHA 30 trainer. He's a lifelong Texan, decorated veteran of foreign wars as you can see from his cap. And RL and his wife have two children, five grandchildren, seven great grandchildren. RL, thank you so much for being on the show. RL (02:59) I appreciate the opportunity to be here. Hari Vasudevan (03:02) Yes sir, yes sir, that's great. So you know, let's get started. You know, you worked for me at ThinkPower Solutions from around late 2018 to early 2023, somewhere around the time frame. You left ThinkPower, you retired to marry somebody you knew from your high school. And you know, you told me the main reason was to... make a new Hari in Southeast Texas? Just curious, is there a Hari roaming around in Southeast Texas? RL (03:37) Not as of yet, and I really told you that because I was wanting you to let me retire. And I told you I would name my firstborn after you. And we will uphold that promise. But I really think there's a reason God gave â“ babies to young people, since we're both in our 70s. Hari Vasudevan (03:58) Okay listen if there is ever a Hari in Southeast Texas I'm fairly certain that guy would be the only guy about named Hari in Southeast Texas. I'm not pretty sure about it. Right? All let's get rolling here RL. I really want to know your origin story right? how you got into the trade, how you got into the industry. give us a quick â“ overview of your start in the industry. RL (04:27) I graduated high school and a lot of young men at that point in time would either go to college or they would buy them a truck and go to work. And that's what I decided to do was to go to work. Now, I graduated, I was 17 and it was not a lot of job opportunities until another month or so. And I turned 18. Now, in the mid-60s, you were not a grown person, he was not grown until he was 21. So at 18, I couldn't drink, I couldn't vote, I couldn't be a lineman, but I could be a lineman's helper, what they are, we affectionately refer to as a grunt. So I had to be 21 because, of hazardous occupation. So, I was looking forward to grunting for about three years. And a couple of years into it, I received a letter from a high ranking government official urging me to sign a contract with the United States government. Hari Vasudevan (05:28) So you were you drafted or did you volunteer into the army? RL (05:32) That's what the letter was. I was drafted. The letter did start with greetings from your president you have been selected. So, I followed the advice of the president and joined the United States Army. It did transfer me to the Far East, which was Fort Polk, Louisiana. Hari Vasudevan (05:36) Okay. RL (05:53) And I took my basic training there and then I moved into my advanced training and what the job they chose for me. And there's really hundreds of occupations that the Army has. They call them MOS. I went ahead and what they chose for me was light weapons infantry, which is commonly referred to as a grunt. RL (06:15) I was 20. In fact, I turned 21 in Vietnam. I'd been in Vietnam about eight or nine months when I become old enough to vote. And I did find out that you could get a hazardous occupation prior to being 21. So, I had to... Hari Vasudevan (06:33) Okay, you could be in the military but you can't be a lineman, right? So, you go to Vietnam just to piece the story together for our listeners here. So, you know, explain to the listeners RL (06:39) Yeah. Hari Vasudevan (06:51) you know what did you do and obviously you have a purple heart cap on give us that story if you will how did the incident obviously there is something behind that story please explain to us give us that story if you will RL (07:04) Okay, briefly, yeah, I had progressed from point man to squad leader and I had some very green troops in my squad and we encountered a vastly superior force and I didn't really want them out on a flank position so I kept them in the middle and I took flank and there's a Vietnamese VC, Viet Cong, was probably a little bit better at his job than I was at mine. And you should never raise your head up when you're facing a superior force too many times in the same position. And I evidently made that mistake. And he was waiting for me and I did take an AK-47 round. Hari Vasudevan (07:53) Wow, wow, where did you, where did you take the hit? RL (07:58) Well, I was, you know, laying down, of course, and it entered my right shoulder and exited my left hip. So, it did quite a bit of damage to the lung, lung, broken ribs, punctured lung. And I was able to get up and move back to where our medic was. And he asked me if I could run and I told him, I don't think so. I didn't have enough air to run since my lung was full of blood. Hari Vasudevan (08:24) You didn't get one lump. RL (08:26) They called a helicopter for me and pretty nice people, gave me a ride back to the hospital. I stayed there for a couple of surgeries. They moved me down to Cam Ranh Bay. Food was a little bit better there. And you don't heal very rapidly in Vietnam, so they shipped me to Japan. And from there, after a couple of weeks, they said, there's not much we can do for you. We're going to send you. Hari Vasudevan (08:41) Thank you. RL (08:51) back to the United States and your tour duty is almost over so you will not have to return to Vietnam. So they shipped me to San Antonio, Brooks Army Hospital. And after a couple of weeks there, they said, know, you're healing fine. Why don't you go home for a month and then come back? And so I decided, you know, I think I'd rather eat mama's cooking than army chow. So, I went home and after a month and I wound up getting married while I was doing this. And then when I went back to the post at Fort Hood, I was married. And so once, I got out of the army, I went back to the power company where I was working as a grunt and asked them for my job back. And they said, yes, we'll give you a job back. We're going to give you your time back. Hari Vasudevan (09:20) Who wouldn't? Who wouldn't, right? RL (09:47) In fact, we're going to give you your military time as it was a good time. I had several years seniority. And so, the next opening for lineman, they asked me if I'd be interested in it. I jumped on it and I started off, I wasn't a lineman, I was a climbsome I was an apprentice. But about four or five years later, I did receive journeyman status and I could legally call myself a lineman at that point in time. And I still like calling myself a lineman and you know kind of Once a lineman and always a lineman. Hari Vasudevan (10:20) Got it. Got it. Wow. What a story. Honestly, what a story. Right. Story of valor, bravery, service to the country. Thank you so much. Obviously, we're all enjoying the freedom thanks to you and your generation, obviously. Right. So and the greatest generation as well. so, that's fantastic So, there you go. So, you joined as a grunt to I guess. Today's Entergy back in the day, was Gulf Power, I guess, right? Is that right? RL RL (10:51) Yes, sir. I had, as a lineman, know, we did transmission to distribution was one word at that point in time. Almost all of the structures were wood. They still I had some steel, but we didn't use specialized equipment. We climbed the poles or the towers and worked them that way. So, I remember one time I came down off of a 225 foot river crossing tower. and they put me on underground job the next day. So, I went from 225 feet there to four feet underground. So, it did make me a well-rounded lineman though. And then I got an opportunity to be a troubleshooter, which was a very good job. I really enjoyed that. Every job was different. And I didn't, I loved being a troubleshooter. I hated the shipwork. So. They asked me if I'd like to go back to the lion crane because they were looking at making a foreman. And so I went over there, they looked at me for little while and asked me if I'd like to be a foreman. So I tried that. a couple of years later, they asked me if I would consider a job in safety. And I'd indicated that I was interested in the safety of safety. Hari Vasudevan (12:05) RL before you get into safety, because that's obviously the bulk of your career, that's how I know you, right? So let's kind of, you know, wrap up our career, your career rather, as lineman, although you're always lineman. So which of those jobs that you mentioned, overhead, underground, and you know, troubleshooter which is the which of those did you find to be the most foreman which of those find to be the most challenging role and why RL (12:34) I think the troubleshooting job was the most challenging because every job was different. You know, the customer would call saying they have problems with the lights and I would go out and listen to the customer. They told me what they thought was wrong. And then I would go back and start investigating myself. it was, and I was by myself, you know, work completely by myself. So, I had to learn to make sure that I did not get myself in a bind. That's what made me very self-aware. And I think it helps me quite a bit when I've become a moved into a safety profession. Hari Vasudevan (13:14) Got it Because self-awareness is critical because you know troubleshooter you're out there figuring out why lights are off, middle of the night, dark alleys so it's not gonna be could be an unsafe environment so, you really have to be self-aware. Is that a fair way to put it? RL (13:33) Yeah! correct. you had to be careful where you walked. You had to be careful certain neighborhoods where they may be unsavoury or drug use or some other illegal activities. You had to make sure you did not put yourself in a position that you could not recover from. Hari Vasudevan (13:55) Interesting. So you know before you get into safety so that I'm pretty sure you had some very interesting stories in your life as a troubleshooter. You know walking some probably tough neighborhoods and whatnot. Give give the listeners and viewers just one one of the most interesting stories that you could share. RL (14:19) Well, there was one story where I was shooting trouble and there was an apartment complex and they bought primary power. But they had one unit out and they had called an electrician out and I finally narrowed it down to where I found a bad transformer. Well, it wasnt a bad transformer it was a bad fuse. And they said somebody had come up and he... put a device on it and it was a big blue flash and he left. you know, you hear a lot of stories from the customers. Okay, I heard that, but I want to investigate to make sure it was true. And I got over, got to looking and what he had done was gonna test a fuse. And it's a big silver sand fuse, a large fuse. he... put his voltmeter on the top of the fuse and the bottom of the fuse to see if it was open. And what he didn't realize it that was primary voltage, which was, you know, 7,620 volts. And his, I did find the burn marks on the fuse. So that was fairly interesting that an electrician would go out and try to check voltage on a primary voltage with a fluke and that's the only time I'd ever seen anything like it. then we call the company, the company he worked for and asked if he was okay and he had not reported his injury to him. So I think, I don't know what ever come of that, but I'm sure they did bring him in and take him to task for that. Hari Vasudevan (16:02) Wow, what an interesting story there. So all right, so, now you got an opportunity, you'll get an opportunity to move into safety. I guess you go to college or something like that, you get a degree or something like that and then move into safety. Is that right? RL (16:18) Yes sir. When I first got into safety, the job mainly was to keep people from dying on the line. And I don't know if you all are... â“ knowledgeable of the incident triangle. That's kind of a triangle where you start off with near misses, so many near misses, and then you come up with, and the triangle gets smaller, but you come up with minor first aid injuries, then you come up with the Osha reportable injuries that move up to disabling, and then the very top of it is a fatality. Well, what we focused on was the very top of that triangle. Hari Vasudevan (16:53) So just to make sure that people are tracking because it's an important part, you have the safety triangle, right? Split up into five parts in the bottom is near miss, right? Am I right about that? Okay, the bottom is the near miss and the next level is injuries, right? Osha recordables, is that right? RL (17:13) Well, first aid reports, you know, falling in there, they get more more serious as they work their way up. Then you come up with those who report well, then restricted to disabling injuries and then the fatality. Hari Vasudevan (17:22) It's top. Got it. And the very top, you have the fatalities, which obviously you want it to be as low of a number as possible, right? Ideally zero. RL (17:37) So, that's what we focused on then and the company I was working with, you we had about 5,000 employees working for that company, but we did have a fatality about every two years. And it was, it was regular, you know, and if you started putting the pieces together, those numbers didn't change much between your, the bottom of the triangle to the top, you know, it like 600, 300, 30, 10 and one. So, we started focusing on the bottom of the triangle. And that's when I realized that there's more to it than just trying to stop electrical accidents. And I went to school, there was a, my GI bill was gone by that time. The time I had run out for it. But in Texas, it's called the Hazelwood Act. And if you're a Texas veteran, you can go to school actually for the rest of your life. And so I went to Lamar University and I pursued a degree in occupational safety and health, which was an associate degree, associate of applied science. And that's a two-year degree, but it took me about four years to do it since I was working days and then just going to school at night. So I did achieve that degree and I graduated with honors actually, because I was a little bit more interested in it than when I was in high school, I guess. And I was married and I didn't have the same distractions as I did in high school. But I continued to pursue my education because as a safety professional, you don't just stop learning. There's lots of information out there. A lot of people have found ways to network with other safety professionals. And we started, there's no competition between safety. I understand companies compete with each other, but as the safety professionals, we did not compete. And we would willingly share our knowledge with other companies and they would share with us. So it was a very good network for doing so and well worth the, it wasn't very expensive either. And it was well worth the money. Okay. Hari Vasudevan (19:47) So you go to school, get your diploma, associate's degree, Before we go further, I think that Texas, that Hazelwood Act, right? Is that right? That actually allows the kids of veterans also to go to school at minimal or no cost, something like that, right? If I remember right. RL (20:07) Yes, sir. You have to be a Texas veteran. You have to go into the military from Texas. And that's what I did. And I made the application and it was really no, no problem at all. where everybody else was writing big checks every semester. I was paying for like, student parking and student activities, which we never used. And I was buying my book, but, â“ I was writing a small check where they were writing. Hari Vasudevan (20:19) Wow. RL (20:34) a lot bigger checks than me. So it was a good benefit. Hari Vasudevan (20:36) Wow! Nice! That's good. Awesome! Awesome! Alright, so you get into safety and obviously we talked about the triangle. The triangle was not where it should be. The top of the triangle I had too many fatalities. So which year was this? What year was this? RL (20:55) This was in the early 80s, whenever I started this, then I completed my degree and I started working toward trying to move that. I never could stop. We still I had fatalities in the company, but instead of every two years, it went to every five years, then every 10 years, we was able to move that time frame. I really think that this is a very good method of you don't just focus on the worst injury, you start focusing on the smaller thing. And that's, know, from stopping people from dying on the line, I started looking at, you know, the chemical hazards, ergonomic hazards. Hari Vasudevan (21:21) and see it. RL (21:37) asbestos, hearing loss, things of that nature. And really it was a benefit to the employees as we started trying to help them with these things where you hear about broken down linemen, you start climbing poles for 20, 30, 40 years and knees, elbows, everything's going bad. We started trying to figure out how can we fix things like that. And the top of the triangle was pretty much taking care of itself. Now we did focus on it quite a bit, but it seemed to move as our incident rates got better and better. Hari Vasudevan (22:17) So it was a clear measurable. So, this was 80s. OSHA was formed in established in 1967. Around that time, lot of fatalities, one in every two linemen like you and I talked about. And then you go to 80s, the numbers improve. So before you go further in your safety career, all right, let me ask you this question. In those days, 60s and 70s and early 80s, was there a pushback to the establishment of OSHA and some of the regulations that they were introducing obviously in good faith right. I'm sure not every one of them resulted in success. I mean I'm sure they had to make some changes adjustments based on real life experience and things like that. But give the listeners an idea as to the initial reception of OSHA by two different communities right? One is the worker angle right? The second is the business angle. How did the businesses handle it? And let me actually ask you for three different angles and the third is the safety professionals angle. So how was OSHA's establishment and the regulations received by employees, safety professionals and then the businesses? RL (23:41) When OSHA first formed, there was a lot of pushback, both from the companies and from the employees. OSHA started coming in and telling the companies, you have to do the things that they had to do, which was not well received. And the employees, know, and I was an employee at the time, and well, how can this politician in Washington know what I do for a living? What OSHA did, know, they didn't sit down and write all these regulations at one time. They went out to industry and said, send me your safety rules And they sent them safety rules And there was a lot of different organizations that had different practices. And OSHA just started writing them into law. One example was that there was a company up north that got... In the winter when the river froze, they would go out there and cut blocks of ice and store it in the ice house to use in the summertime for cooling their water, making ice water. Well, they had a rule because it was not potable water that ice could not come in contact with the drinking water. And so OSHA made it a rule, which made it difficult for anybody else to make ice water. Hari Vasudevan (24:45) Okay? Ice could not come in contact with drinking water. Is RL (25:00) OSHA finally realized that they had some rules that are not Right. They had to put it in the container, seal the container, and drop the container into the water. Hari Vasudevan (25:19) Huh, interesting, interesting. So that is obviously the unintended consequences of some regulation that was drafted by OSHA, right? And then I'm assuming that got fixed, right? They fixed it. RL (25:32) Yes, they're in. And OSHA should reduce thousands of their rules, you know, to try to make them little bit more understandable. And then they started putting groups together to study the rules. And they're still making changes. Just a few years ago, they made a lot of change. The construction industry and the general industry, which is two different rules in OSHA, and they had different regulations, like different approach distances and things of this nature. But linemen, when they went out working, depending on what they were doing, they would move from the construction to general industry, sometimes back and forth during the day. Kind of an example. Like if you replace a light bulb, that's general industry. But if you went over there and replaced that socket where you had to go in and work on the wires, that's construction. If you went out and replaced the 30-foot pole with a 45-foot pole, you went from general industry to construction. So the rules bounced around quite a bit and made it very difficult to come up with a rule and a process for people to go out and work. So OSHA came back and they made us rules mirror images of each other. They made a lot of changes. In fact, I was working for a company at that time that asked me to find out what changed. And I got to look and it was 1,600 pages. And so I got the opportunity to read 1,600 pages of OSHA regulations to see what changed. And I found that there was quite a few changes in there. But it makes it easier to follow the rules. Hari Vasudevan (27:19) Yes, no, can actually, I do have a question which I'm gonna hold my thought because I wanna finish this conversation before I go to that follow up question. So, pushback from employees, pushback from definitely businesses because it made it harder, you're putting checks and balances in place which businesses generally don't like, right? What about safety professionals? People like you in your profession. Did you like what they were doing? OSHA was doing. RL (27:46) It made the job easier sometimes when I had the force of law behind me, but it's still kind of aggravated me because I was the safety professional for a line group. And I still I had those people telling me, but actually one of the things that we do right now when we teach OSHA outreach, you're in construction, there's about two hours you had to spend on introduction to OSHA. And I have really changed a lot of people's minds when I started showing them. the incident rates for pre-OSHA and post-OSHA. In fact, it was during the height of the Vietnam War. And when they were trying to get Congress to okay, because, you know, this is an act of Congress to establish OSHA, they said the two most, The two activities that caused the most fatalities in young men is the Vietnam War and working on the job. It compared those. Hari Vasudevan (28:52) Wow. You know, a couple of things here, a couple of follow up questions. You're talking about complexity of OSHA, right? You know, even today, honestly, RL one of the questions I have jumping to today and then let's go back to your career. You know, I see safety manuals sometimes become very complex, right? Because you write a safety manual, your client comes in and says, hey, we need this section. You add a safety section. And yes, intent is always good. But how many people can read 700, 800, 1000, 1500 page long safety manual and then, you know, companies expect employees to read it onboarding. They say, sign off on reading the manual. It's you know, it's impractical, right? It's just like the fine print of any software that you sign. You never know really what you're signing up for. Why is that still the case? Are we going back towards a complex situation unintentionally and is that going to come back to bite us down the road? RL (30:03) The potential is there and you know, like the EPA, Environmental Protection Program, prior to that, we had rivers that would catch on fire. I went to work in the power industry in a highly industrialized area called Port Arthur, Texas, lots of petrochemical foundries and some of those Hari Vasudevan (30:26) I've done it. RL (30:29) when rain would come up and you was wearing a white t-shirt, you'd get black, the rain would leave black spots all over your shirt. it was that bad. They have stopped all of that, but it's possible they have went too far with it to really cripple industry, you know? So you had to temper what is, you know, You will never get 100 % risk free. There's always some risk involved. We cannot legislate risk free. you were the thing that injures lots of people every year is the act of operating an automobile. But we are pretty much set up to where we have to have that every day. Hari Vasudevan (31:01) Yeah. RL (31:21) But the fatality rate for automobiles is really outstanding. â“ Hari Vasudevan (31:26) Yeah, it's crazy. You know, let me ask you this. mean, talk about regulation. Why is it that, you know, people, I mean, I took my phone here. Why is it people are looking at a phone like this, literally like this and then driving? I see them every day. It scares me. Why are there no laws that make it illegal? I'm just curious. RL (31:55) In fact, the only laws that I know of is during in school zones where you cannot talk on the radio or you can't use the â“ phone. You can't utilize it. I don't know why, know, that they a lot in a commercial vehicle, you can't use a phone. I think you can use hands free, completely hands free, where you tell it who to call and it will call for you. But you're absolutely right. I've seen people where they're holding it up over the steering wheel and steering with the back of their hand and reading or are watching movies on it. Hari Vasudevan (32:35) It is genuinely crazy. OK. So we've talked about the complexity. We talked about EPA. It's kind of beautiful. Right. OSHA. They kind of over overregulate and pull back being practical. Come up with safety manuals. Maybe they're trending towards being too big, too much. let's see if that gets a pullback, right? And then you we talked about EPA maybe overregulated, right? Because we have to have industries thrive. know, so businesses push back but I'm assuming over time, in time, because of the benefits that safety invariably has in any business. Right? I mean you talk about the triangle. You go from one fatality every two years in your example to you the last number I heard you say was 10. So when that number increases at the top of the triangle or rather the top of the triangle, the numbers decreases to zero, but the zero remains for a longer period of time. That's good for business because your trained employees are there longer. You don't have injuries, which injuries cost money, liability, know, insurance rate goes up because, you know, injury, OSHA recordables has an impact on EMR. Total Recordable Incident Rates, TRIR, all these things. So over time, I'm assuming, businesses and employees turned around and came around to believe in the mission of OSHA. And it's a good thing to be safe, I'm assuming, right? RL (34:17) And I know employees have appreciated OSHA, you know, whenever they have prohibited some very unsafe acts. They still have not regulated how many hours in a, if you're driving a commercial vehicle, you can only operate so many hours a day, but they still have not stopped. lineman from working 24 hours or greater. â“ I think, you know, there's still room for improvement. And there's things that can be done to help. And I think we are slowly moving in the right direction. Hari Vasudevan (34:46) It's yeah. You're right. Yeah, you know that is something that you hit a good point out there because a couple of things, you know, when you were leading the health and safety program at ThinkPower Solutions, we participated as a company in the suicide prevention week because suicides are one of the, it's highest in the construction industry, if I remember right, right? It is the highest of all industries. Suicide is highest in the construction industry. my guess you probably know the facts on this better is because long days away from home long hours like you just talked about right in touch upon that topic right some of the issues in the construction industry obviously that extends into the line industry can you talk a little bit about that RL (35:44) The hours of work, a lot of our people are driving a commercial vehicle, which limits their hours of work. But whenever a storm, major disaster, something like that takes place, the hours of work, several of those regulations are after a declaration of emergency, a lot of those regulations go away. Now, I think a lot of the companies have realized that it's unsafe to work people 24 and greater hours. I have worked like that before and I was making mistakes after a period of time that today I would run somebody off for making those same mistakes. I was just, you know, completely exhausted. Now think a lot of the companies are starting to limit how many hours they want to work people, even if there's a major disaster. a Hugo hurricane, Hugo or something like that. They still have found it. You know, if you work them too many hours, you start losing productivity. So given them about eight hours off every 24 or something similar to that, giving them something to eat. lot of times they, they forget about the, you know, the trucks need to be fueled and so did the line hands, you know. Hari Vasudevan (36:47) Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, yeah, no. know, mistakes creep in. mean, our old friend Jeff White always used to say from a human performance angle, a normal human being makes about three to five errors in an hour. But when the same human being in a highly stressed environment makes 12 to 15 mistakes in an hour. Right, so you start working 15 hours, 20 hours, 24 hours. Clearly, you get stressed and more mistakes creep in. And the idea is when you make three to five errors, they can be small enough and the number of errors is only three to five. When you make 12 to 15, you quadruple the chances of some of those mistakes being fatal. right? That's the problem right? So it's a really good point out there. So we were in the 80s and then so you continue your career in safety just keep going RL RL (38:00) Yeah, when I said that we have went from, when we first moved from telegraph and telephone linemen to power linemen and we had one in two fatalities, and now we've got one in 2,000. And we say, man, look how good we've improved, and you puff your chest out and say, we're doing great. Unless you. happened to be that one in 2000 or closely associated with that one in 2000. So, we're always gonna have to improve. Hari Vasudevan (38:28) So just for the listeners here, just for the listeners, one in two is 50 percent. So if you're going into the line trade in the 60s, there's a 50 percent chance you're going to die on the job. Whereas now it's one in two thousand, which is zero point zero five percent. Still high, right? But. just look at the difference, the impact that health and safety has had. I just want to emphasize that point. You keep going. Alright. RL (38:59) Yes, OSHA has done quite a bit for us. And I know sometimes we think they've... have gone overboard, quit preaching and went to meddling is what we used to say. OSHA doesn't necessarily mean our savior has arrived. They still have to go out there and act like a police force. And when they first came into being, they had to do that. They had to let everybody know that, this is a government organization and it does have some power. So, they did and people could potentially go to jail if they have problems. â“ Don't comply. Hari Vasudevan (39:37) Wow. RL (39:42) Now they're more trying to help. I have ran across lots of OSHA compliance officers when I was working major devastations, hurricanes, things of that nature. They would come in and they was not pulling out their ticket book and writing citations. They will come in and start talking with you. And sometimes they would tell me something, hey, that's a great idea. We're going to do that. And sometimes they'll tell me something, no, that's impractical. We can't do that. But, you know, and I've convinced them that it's not required by law, but actually it's not required because it's impractical to do. They try to help us as much as possible. I have never ran across an OSHA compliance officer that I could not get along with. Hari Vasudevan (40:28) Yeah. RL (40:32) I was still working for the power company and they called me up one time and asked me to go help them with a fatality that they had a new compliance officer that didn't know anything about line work and would I go help her And I did go over there and work with them, You know so, that shows that I've kind of developed a rapport with them and I've not really tried to hide from them. I think that their hearts in the right place. They're trying to help. And I think they're a bunch of dedicated, say, professionals. Everyone that I've run across. And whenever I'm teaching OSHA compliance training, â“ OSHA I always emphasize that. I spend the whole two hours kind of singing the praises of OSHA because they have done so much for us over the years. Hari Vasudevan (41:07) Yes. Yeah. RL (41:22) Even though they're aggravating you, it's not. Hari Vasudevan (41:23) Yeah. Yeah. I know one thing. You are you're one of the biggest advocates of OSHA. Obviously, you've seen the evolution of the safety industry. So rightfully so. so from there, obviously, you had a super successful career at Entergy. And then. you retire from Entergy, you go on to continue your OSHA 1030 training and things like that. And then 2018 comes and the company I was running at that time, ThinkPower Solutions, we were unfortunately involved in an incident in Texas which has since been resolved. But anyway back in 2018 there's a big issue. We about to be pulled up in front of major players at Entergy. We got introduced by our common friend Jason Riddle and we were about to go to meet the fire, meet the heat. with Entergy a couple of days later. And to this day I don't really know. mean obviously deeply grateful for joining us. I still can't believe that you joined. Nobody would have â“ touched me, touched the company with a hundred foot pole. You joined ThinkPower and then you really established a safety culture because we were a young company at that time. growing rapidly and you established this really great safety culture that to this day that helps the company being entrepreneurial, psychologically safe, super important piece of the puzzle, right? Employees were comfortable sharing what they saw, the stop work authority and whatnot. So... That being said, why did you join the company in 2018? Because you were, you're literally, I remember you were about to go to Oklahoma and teach OSHA class, you cancelled that, came to face the heat at Entergy Explain to me that. RL (43:16) Well, I did not really want to go work at fatality because that is really not good work. I have unfortunately worked several of them and it just take a toll on you. But you sounded like you, your heart was in the right place. You wanted to try to do the right thing. And so I said, okay, I'm going to help you with that. And actually I thought, whenever that was over with, you was gonna let me go. And you asked me if I would stay on and try to develop a safety program for you. And so, I did and thanks. You were very receptive. It was a pleasure working with you. I am really can't sing your praises high enough because you did have an empathy toward the people. You wanted to make sure that they would work in it without hurting themselves. And we spent a lot of time on that and we got the employees to help us with that. Those terrible moments where they said, hey, this can hurt you, watch out for it. And it's a whole lot easier. I think it carries more emphasis if one of the employees says, hey, don't do that, that'll hurt you, then a safety man's saying it. Hari Vasudevan (44:37) Yeah. RL (44:37) You know, like whenever you was a teenager and you wanted to borrow the car and your daddy said, â“ okay, you can borrow the car, but I don't want you drinking in there. And you're oh daddy, don't worry about that. And you're thinking the whole time, daddy's idiot. I'm going go out there and score me some alcohol as soon as I can. But if you get in the car and one of that, you say, Hey, let's go get us some beer. And one of the hands and man, we better not, you know, â“ we could get in trouble. That carried a lot of weight. And I brought that into. These companies that I've worked with, it's let them tell us what's wrong. And it seems to work well. Hari Vasudevan (45:11) Yeah, and obviously your career itself starting as a grunt, know, growing in the line trade, becoming a journeyman lineman and then getting into the safety gives you the credibility to do what you do. Right. So that's that's an important piece of the puzzle there. So. Let's get into auralisms because you and I have written a few articles together about safety. Educate the audience, educate the listeners about the auralisms you got. RL (45:38) Okay, there are a lot of things that I used to try to come up with. I'm kind of a country boy and I like to keep things simple. And I come up with some of these ideas that RL (45:50) 90% of the rules are written for 10% of the employees. That doesn't sound right, you know, but actually only 10 % of the employees are going out there, violating rules and hurting themselves. But I want to ask the audience a question. Have you ever partied a little bit too much the night before and you showed up for work the next day, still under the influence? Have you ever sit up with a sick young one all night and you're really exhausted? Do you have an elderly parent? that you're waiting on that phone call and that's on your mind. If you could tell me that, yes, I have fallen into that, you are part of that 10 % at that point in time. I will look you dead in the eye and tell you have been in that 10%. The trick is you don't live in that 10%. But you have to be thankful that somebody has put some redundant rules in place that helps you make it through that 10%. Hari Vasudevan (46:37) Yeah. RL (46:48) So when I say 90 % of the rules are for 10 % of the people, that's what I mean. Hari Vasudevan (46:49) Yes. Yes. So the idea just expanding to the listeners here is that doesn't mean only the rules are applicable to 10 percent of people. 100 percent of the time it is generally applicable to 100 percent of the people, but only 10 percent of the time because for the most part you're in good health, good spirits, get a good night's sleep and things like that. But There are days when you wake up like, hey, taking care of your sick child or taking care of a sick parent or whatever could be the reason and you're not 100 % focused. So your rules help you in those 10 % of the time. Is that the right way to put it, RL? RL (47:39) Yes, that's a good way. And that's the reason you helped me so much on those articles, because you did take the country out of a lot of those articles and make me sound like a professional. Hari Vasudevan (47:50) Alright, what is the other one? RL (47:52) Another one is, well, I would call it the Rule of Should. I've been writing safety rules for a long time, and there's normally two types of rule. One of them is a should rule. This is a good idea, but you can deviate from it if there's a good reason to. The other one's a shall rule, which says this carries the force of law. We don't have the authority. We have to follow this to the letter. But I think the most important one is a should rule, not necessarily either one of those rules, but the rule of should. Whenever you're out working and that voice of self-preservation tells you, you know, I should reposition this truck so, I can reach it easier and safer. I should reposition my ladder. I should put some additional covering on there. I should take this extra step. That's when That rule of self-preservation is telling you, you should do this. That is, in my opinion, the most important rule there is. And if we could all follow that rule of should, where we're telling ourselves this is what we need to do, then we could probably do away with safety people and a lot of our safety rules if people would just follow that rule of should, where you're thinking, this is what I should do. Hari Vasudevan (49:07) Got it. Got it. OK. That's great. And is there any other auralisms for the audience here? RL (49:15) Well, I've always said that no one violates a life-threatening rule. And I know that the people listening to this have been involved, closely associated with a very serious accident where rules were violated. And they say, well, that's silly to think that no one violates a rule like that. You will not violate that rule if you think you're going to get hurt doing it. You think you're good enough to violate the rule. And we've got safety, lying people here that's so knowledgeable and so skillful that they can dance around those rules. And you can get by with that almost every time. But once when you happen to be in that 10%, or if somebody else does something inappropriate and you don't anticipate that, that's whenever you can get in trouble. That's what I mean. is no one violates that rule if they think it's going to hurt them. When that rule of should, when that rule of should kicks in, that's telling you that even though you're a skilled professional lineman, that you need to follow that rule. You need to do something different because that rule of should's kicked in for that self-preservation. Hari Vasudevan (50:31) Got it great, great words of wisdom, obviously, from a long time safety man. I actually remember you wrote an article with that exact title. Words of wisdom from a longtime safety man something like that right so all right so let's I know you still enjoy teaching you still do your OSHA 10 and OSHA 30 training and at the end of the show we'll give people your contact information if you so choose to they can choose to reach out to you Hari Vasudevan (50:57) So let's kind of get into safety. We know that, you know, sometimes risky job site behaviors are prevalent. for variety of reasons. People work long hours. As you know, people work more than 30 hours at a stretch sometimes during storm. People stay away from their families for long stretches of time in this industry. you know, there are other, you know, people drive a lot of miles, lot of hours, and all this could lead to stress and obviously potentially more mistakes. Is there a role for AI? to humanize construction, right? To humanize the utility industry. Can we use AI to nudge different stakeholders of a project, project managers, health and safety professionals, and others in the leadership team to say, hey, you know what, this crew out there or this employee out here has been working too long a period of time or has not gotten a break. and stayed away from home for long periods of time. So this could lead to potential safety issues down the road. And that nudge can potentially â“ help decision makers to help â“ keep the job site safe keep the crew safe, to keep the employees safe. What's your take on that? I'm sure you've kind of experienced a lot of this data analysis in your 40 years of health and safety industry. RL (52:23) And that's very interesting. I've never thought of that particular, you know, using AI to do that, but it is predictive. And I did similar work with an Excel spreadsheet, and so I could massage your data a little bit, but it was really time consuming to try to do that, and you had to make sure you ask it the right questions. with AI, that may really make it a lot easier for us to predict. When it's time to give somebody a break, when it's time to give them a safety message, when it's time to let them call home and talk to their wife. And you spoke of suicide rates and things like that, but in our profession, the divorce rate is very high. A lot of that, the class. Hari Vasudevan (53:09) Huh, that's super interesting to know actually. Divorce rates are very high as well. RL (53:15) And it's hard on family life. I missed in my career, I missed a lot of birthdays, anniversaries. I missed holidays. That does have an impact on the family. anything like that can have an impact. then if family does separate and divorce, that's a very traumatic occurrence for the guy working and his mind is. or her mind is not necessarily owned their job at the time. â“ a lot of things can impact that. And divorce rates, you know, it's pretty personal and you don't really share that necessarily with the, make an incident report on a divorce rate. But things like that can happen. And if we can learn to temper our zest to try to get the job done quickly and done properly and get lights restored, things like that, because really, once you have major devastation, you can't go into a 7-Eleven and buy a pack of smokes. know, everything is shut down. So it impacts a lot of lives. And so there's a lot of desire to go ahead and get everything completed. And sometimes we push ourselves too far. And it's not necessarily the company making it do that. Hari Vasudevan (54:19) Yeah. â“ RL (54:31) It's our own desire to do a good job that does that. â“ Hari Vasudevan (54:36) Let me me let me ask you something here if that's OK. So you know, have you done any analysis in your long career? Is there a group of people that get hurt more often get hurt more severely and could AI be used to predict that and help keep the job site safer? RL (54:55) Yes, as a matter of fact, I did a lot of that when I was working for a power company. And it was pretty good sized power company covering four states, but my territory was Texas. So I was utilizing my data and I was, know, OSHA requires you to collect the data, but it doesn't tell you what you can have to do with it. And so I was trying to get that data together. I had a theory that younger people had more incidents. But the â“ more seasoned people had more severe incidents. And so I started looking at it from there. Hari Vasudevan (55:27) Did your data prove it out RL? RL (55:31) It did. It showed that the younger people did have a lot more, but the more serious, the ones that were in lost time or restricted duty or even worse were people that had more experience. And I think they were relying on their experience instead of, you know, and you can get by with that almost every time, but it's one... like that ruler should that 10 % that the safety rules were written for, but that is a sliding scale and everybody's in that 10 % at one point in time. And even if you're in the season employee and you happen to be in that 10 % that day, it's something unforeseen occurs and you don't recognize it and you can get hurt. I think that's what contributes a lot to that. But the data did show that more seasoned people had more severe incidents. â“ Hari Vasudevan (56:30) Yeah, that's interesting. So, you did the analysis yourself manually using spreadsheets. There's tons of data out there now that OSHA has been established many, many decades ago now. We brought the fatality rate in the line industry from 50 % to, I think we did the math, it's now 0.05 % or something like that. so, we can actually move the needle further. if we use AI effectively, crunch the data and nudge the different stakeholders in a project and help them take a break or help them go home to their families and things like that can make it easier. Because candidly speaking, from financial standpoint, which I've dealt with in running companies and running projects, there are perverse... incentives out there for project managers and companies as well, right? Because the longer employees work, sure, they get a bigger paycheck, but so does the company. The company makes more money. On the other hand, there is always that risk that comes when employees work longer hours and stay away from home a lot longer. It might not happen all the time, but it does happen as your data is proven to be. So if the employees â“ you know going to be safer if the divorce rates are lower the suicide rates go lower because of these nudges that means that â“ you know it's worth the you know trade that we are making as an industry to in the short term yeah sure economic benefits may not be that great you may make less money but in the long run you're keeping them you know a family together you're keeping you know, the employees safe, the crews safe, and that is a big economic trade that most companies, I would do it, and most companies would do, and if AI can help us get in that direction, I think it's a great way to use AI in a positive way, don't you think? RL (58:30) I agree and I did the same kind of database with vehicle accidents. And I did determine that there was a particular time of day when almost a big percentage of them occurred and a particular day. And so I started putting an emphasis program where the dispatchers had them on all channels, all talk groups, give a safety message on driving. at that particular time and I was able to make some changes. We still had some vehicle accidents. never was able to go down to zero with that, but I was able to change that day where I put the special emphasis. I quit having them at that day or that particular time. So there's things that you can do that's not necessarily gonna cost the company money. It's just to give a safety message on occasion. Tell everybody to pay attention. Take five minutes and call you home. Just call to your wife, talk to the children. Reconnect with them. Take a break and go drink you a cup of coffee. Sit down under a shade tree for a while. There's things you can't do that's not gonna cost the company a great deal of money. Hari Vasudevan (59:37) No, I agree with you on that. think if AI can help us analyze data and keep us safe. mean, because when I took defensive driving class, I remember recognizing that, hey, majority of accidents, a huge number, I can't recall now, but a very big number, more than 70%, 80%. Accidents takes place much closer to home, which you may not intuitively think, but you do can. tend to relax as you get closer to home, known roads and whatnot. So that causes more accidents closer to home. So these kind of data is out there, can be analyzed, AI does, makes our job easier. It nudges different stakeholders in a much, much more easier manner, robust manner, and hopefully we can use that to make the industry safe. That's a phenomenal way to look at it. So let me ask you a little bit about... â“ I know you're super generous with your time to come on this podcast and listeners are going to benefit greatly from this, right? Have you ever been on a movie before? Have you been a movie star before RL? RL (1:00:40) Well, actually, I was asked to help out on a movie. It was called Life on the Line. Now, it wasn't readily accepted by a lot of the linemen, but Hollywood did get their input in there. My job was to actually say, okay, this is possible. No, this is impossible. We can't do that. And John Travolta was in the movie. A lot of very good people was in the movie that... And I was actually in there, that was part of my, that was my compensation, I guess. I got to sit in the movie. It was a bar scene with the bikers and a fight going on. And John Travolta stood up and the biker stood up. And at that point in time, everybody in the bar stood up, they were lying in. But that was actually based on some experience when something like that actually occurred for one of the locals. Hari Vasudevan (1:01:12) Yeah. RL (1:01:29) Several of them stood up and everybody in the bar stood up and everybody kind of calmed down then. So that has happened. But yeah. Hari Vasudevan (1:01:37) Man, so you're a movie star and we're honored to have you on the show, my friend. RL (1:01:44) â“ well, actually, if you look at the credits for they, they, know, everybody's name comes through and what they did under lineman technical advisor, you'll see RL Grubbs. So I did get my name in there. So that's one of my one shot at fame. Hari Vasudevan (1:02:00) So the name of the movie is Life on the Line, right? John Travolta and there you have it. RL, which stands for Real Lineman, Grubbs was on a movie and he's gracious enough, generous enough at this time here today as well. RL (1:02:03) Life on the line. Hari Vasudevan (1:02:18) let's kind of go into some rapid-fire question you ready RL (1:02:22) Yes sir. Hari Vasudevan (1:02:23) You're getting nervous? RL (1:02:25) â“ A little bit. Hari Vasudevan (1:02:26) You know, come on man, you've taken a bullet and you got a purple heart you can't be nervous I'll tell you what, you've always been impressive. You always amazed me, impressed me with your ability to use technology. For a guy who lives 17 miles from your mailbox, really out there in country, you do handle technology pretty well. So that's pretty impressive. So tell me this, So when... RL (1:02:46) Ha ha ha. Hari Vasudevan (1:02:56) when a mailman comes and wants to deliver a package, does he give you a call from a mailbox? Do you have to hop in the truck and go to the mailbox 17 miles and the mailman is sitting there smoking a cigar or how does it work there? RL (1:03:13) Well, actually, There was times because there was a mailbox within front of a house and a lot of times they just put it inside the fence, any package I And it took them quite a while to make sure they understood, look, there's several mailboxes there. They don't deliver back down to where I live. So putting them in that man's yard is just going to aggravate him because he's either going to have to Hari Vasudevan (1:03:34) I'm RL (1:03:39) move around them or bring them to me. I finally convinced a lot of the agencies that, you know, give me a call. I will go come get it. Or a lot of times now they're just putting a note in the mailbox and say it's at Silsbee Post Office or something and I can go there and pick it up. Hari Vasudevan (1:03:58) Interesting. You know, I think our friend Jason Riddle has the same issue. He once complained to me that, the turkey you sent me for Thanksgiving, it got spoiled by the time it came to my house. I said, my friend, it's because of where you live, my friend. There's nothing much I can do about it So anyway, continuing our rapid fire questions here. professional sports or, you know, high school, college sports. RL (1:04:25) I really high school. I like the high school football. I got a grandson playing. In fact, I went to scrimmage yesterday evening. We drove over there to watch him. I like before they get in there and making a living doing it, know, high school football, high school basketball, little league, even you know, with the young ones out there with the T-post, you know, that they're, hitting the ball. I really enjoy going and watching those more than I do the, the professionals. Now I do ride over to Houston on occasion and watch, the Astros play because I, you know, they're kind of, they're only about a couple hours away and kind of a hometown team. So I do like the Astros. Hari Vasudevan (1:05:13) So you definitely like the Astors of the Rangers, right? So that's good. So let me go back to your grandson. What sport does he play? RL (1:05:20) uh, he plays defense, uh, lineman. he's just, 14 now, but he's a big old boy and he does well with it. he's, I always thought he was too soft spoken and kindhearted to be a football player. was telling my wife, said, you know, if he hits somebody, he's going to probably apologize to him, but, uh, he really takes into it. He was working going to a small school. He's moved to a larger school now. parents moved, but he joins the band. And so he was playing football and half time he would have a tuba and he was marching in the band out there. So he didn't get much rest, but I think now he's just focusing on football. Hari Vasudevan (1:06:00) Really? That's good. Interesting. We'll look out for your grandson one of these days. Obviously Texas is a you know, ground for football players to come up, right? Come up through their ranks. High school. So that's great. Astros fans. So let me direct you an Astros question. I believe they won two World Series, right? Is that right? that? RL (1:06:25) Yes. Hari Vasudevan (1:06:27) You know RL you might be surprised I've been to both those World Series one game each actually. I believe I went to game five of the 2017 World Series. took you know if you remember Jesse Guzman I took him and a couple of customers and I did take again Jesse and a couple of customers to the 2022 World Series. I believe it's game two if I remember right. So the game five was a thrilling game. 13-12 Astros won in the 10th inning extra inning against the Dodgers. So 2017 World Series versus 2022 which one was sweeter for you? RL (1:07:06) I really enjoyed all the games. They're all nail biters right there toward the end. I've always heard that the game is not over until the last out takes place. And everything can change. The game's going into overtime and things. I'm not sure which one I would say was the most exciting, but I really enjoyed Sometimes if I was on the road, I was trying to find a radio station that I had carried them so I could listen to the game. It's just something I enjoy doing. I enjoy listening to the game or watching the game. And I enjoy watching it on TV as much as in person. Hari Vasudevan (1:07:45) So you're not gonna... So you're not going to pick one, but that's all right. But the next question you got to answer. RL, you're president for a day, my friend. You have full control of Congress. House, Senate. What's the one thing you will do? RL (1:08:03) Ooh, okay. If I got full control, as a Vietnam veteran and an Army veteran, I really have a soft spot in my heart for old soldiers. And I do know that there's a lot of these old soldiers that are on the street. They have some problems. I know that a lot of people A lot of soldiers are having difficulties from injuries, exposures to chemicals. Recently, I was diagnosed with leukemia because of exposure to Agent Orange. They did take care of me well, didn't cost me anything. And I was seeing the bills about $100,000 a month and I was paying nothing. All I was doing was just driving over and getting my chemo and stuff. So I would try to do something to improve the status of our veterans. Hari Vasudevan (1:08:59) Got it. It's a really good thing to do. And you know, it's great to see you. I know you were diagnosed with leukemia. I know you went through chemo. It's great to see you on camera and doing well. And I'm glad to know you're in remission. that's a great thing. So that's local. What would you do one thing internationally? Obviously, America's the world's superpower. What would you do internationally? RL (1:09:24) I guess I'm glad I'm not a politician. Now I have kind of an amateur politician and I've always said, okay, that's not the right thing to do. I'm real concerned about our welfare program and it's so easy. Anytime you come up with a rule to help someone, you open up an avenue for somebody to exploit that. And it's very difficult to weed through those and see which ones are real, which ones are, fraudulent. Yeah, I'm not sure how to fix that, but you know, I really worry about some single mother not being able to feed her children because of some, we're trying to fix, keep somebody from exploiting that route So I don't know how to fix that, but I would like to put some people in looking at how can we fix something like that. Hari Vasudevan (1:10:21) Interesting. That's a good thought. That's a good thought. Listen RL Grubbs, that is a pleasure having you on the show. Honored to host you on the show. If people want to reach you, I know you're a certified OSHA 10 30 trainer. What is the best way they can reach you? RL (1:10:39) Well, the best way would be to email me because I've really been getting so many spam calls. put do not disturb on my phone most of the time, but you can text me at 409-656-3133 or you can email me at Texas safe. That's what I was using whenever I first started consulting, texassafe@aol.com And now you had to spell it out, Texas and safe. It's, yeah, there's a double S in there. A lot of people will leave that out. So that I would, really enjoy that. I enjoy teaching and I've tailored all my classes to the line industry. So and I try to get the audiences involved as possible. It's a lot easier teaching seasoned lineman. And it is teaching and I go over and volunteer at a Lima school not far from here. But these people were making hamburgers yesterday and they're learning how to build power lines today. So it's kind of hard to get their attention. Hari Vasudevan (1:11:49) You know you need more of lineman now because you know because of AI the thirst of power is going You know, I don't know if you know, but the industry has invested $1.3 trillion from I believe 2014. It's going to invest $1.9 trillion by 2029. It's just crazy. I mean the amount of power that these data centers need. So yes. What you described is going to happen more and more. They're going to be flipping burgers one day and they're going to go into the line trade tomorrow. So we need safety professionals to keep the industry safe. For the audience again, RL's email ID is And my friend RL Grubbs, you know, I can name a handful of people who made a significant difference to ThinkPower Solutions. You were one of them without a doubt. You just made a significant difference. Deeply appreciate the effort that you put in. RL (1:12:52) Well, I appreciate the kind words. Hari Vasudevan (1:13:02) and appreciate the relationship, appreciate the leadership, appreciate your service to the country, service to the world and great to see you back in full vigor. Glad to know you're feeling great and you stay safe my friend. RL (1:13:17) Okay. I appreciate that. And I ended almost every safety meeting I've done for the last several years. I say, and I appreciate all's attention. And you be careful now you're here. Thank you. Hari Vasudevan (1:13:30) Yes, sir.